Trust-centered Community Pt 2: Sociocracy - Intent & Structure

“Free circulation of information is essential to healthy self-governance.” ~ Joanna Macy summarizing Karl Deutsch

Sociocracy is a governance system that prioritizes equality and consent in decision-making. It involves organizing groups into self-managing circles, where members have equal voice and power. This decentralized approach fosters trust, collaboration, and adaptability, leading to more effective and sustainable organizations. Sociocracy is particularly valuable in today's complex world, where diverse perspectives and shared ownership are crucial for success.

Consent is required for all policy decisions for many reasons, principally: it ensures (1) that all group members are able to participate in the decision-making process without feeling oppressed, and (2) that the decision has unanimous support. No one can be excluded. (T. J. Rau, 2023)

Consent

Consent in sociocracy is defined as “no objections,” in that no participant finds a policy decision to be incongruous with the stated aim of the policy. Consent is reached when everyone agrees that, at minimum, they can work with the proposed policy.

When an objection arises, it is the group’s responsibility to find out what is underlying the concern with a neutral stance. The objector states their reasoning for objecting and the group determines whether it’s a preference or true objection. See the next installment in this series on On Objections, Preferences & Consent for a more thorough explanation of the difference between an objection and a preference.

The decision making process happens in three phases:

Understand - ask clarifying questions

Reflect - offer immediate thoughts and suggestions

Consent - determine whether the objector is on board to try it out

If true objections arise in phases 2 or 3, they must be addressed, and the proposal must be modified to alleviate the objection. Such modifications might include:

Testing the proposal for a short “experimental” period before making it official, and/or

Moving forward with the proposal with a clear system for tracking whether the stated concerns bear out, and if so, determining the appropriate action to amend them.

The goal is to find a workable solution, and not have perfect be the enemy of the good.

Structure

Sub-Circles

Decisions are carried out by sub-circles that adjudicate a particular domain. Each circle can have as many members as needed, though an optimal count is 4-8 people. Each member can alternate between four official roles:

leader - oversees operations and makes sure the circle works towards its aim. This is the top-down link that fields actions from other circles to the circle.

facilitator - moderates the meetings

secretary - takes notes during meetings and makes sure the circle documents are up to date

delegate - represents the circle's voice in the next-higher circle. This is the bottom-up link that fields actions from this circle to other circles. (T. J. Rau, 2023)

The General Circle

The General Circle is composed of the linking roles -- usually leaders, and delegates -- from the sub-circles. This coalition ensures each circle has the necessary resources and knows its aims and domains. The General Circle can’t override other circle’s decisions.

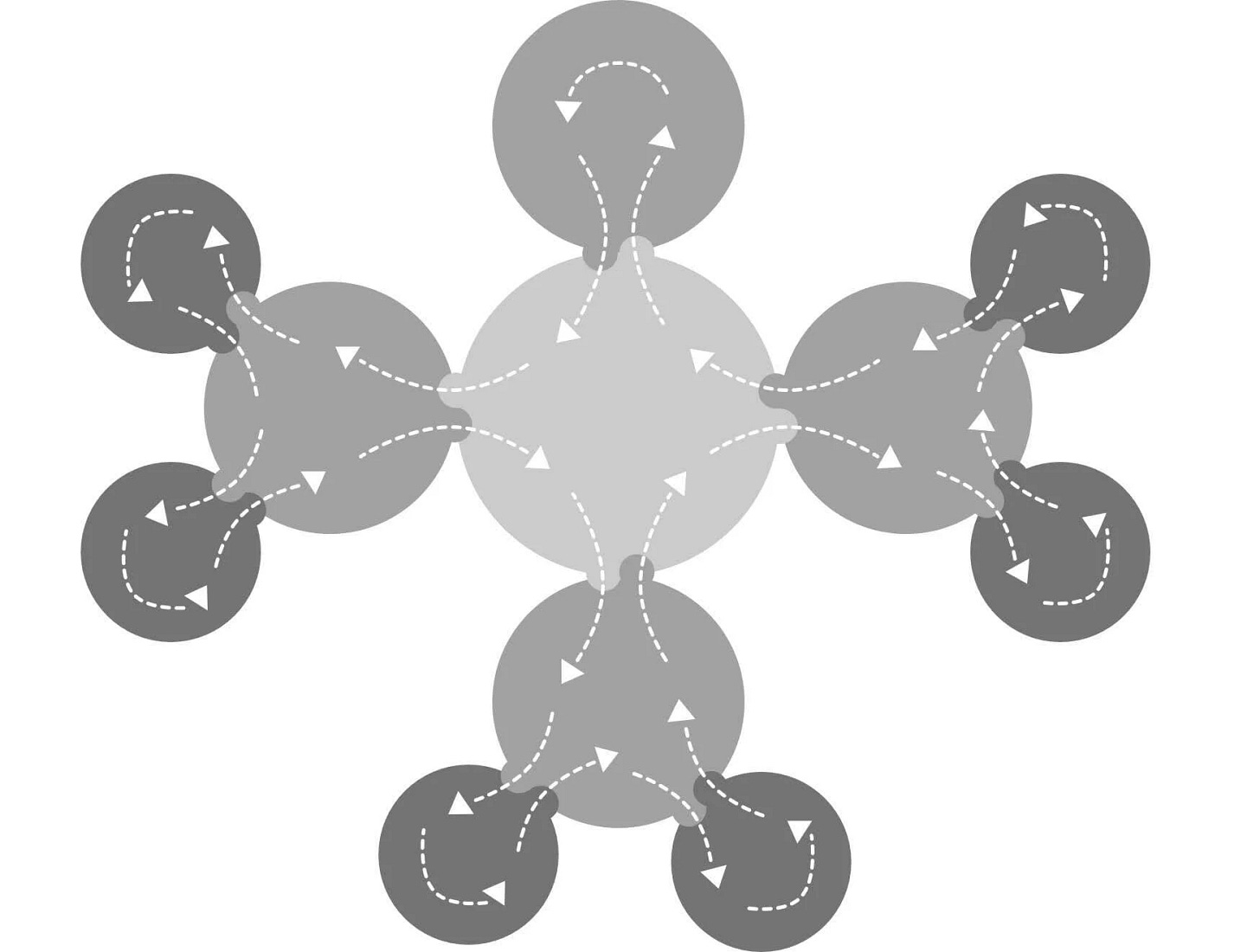

Distributed Circle Structure

All circles are autonomous and exist sans hierarchy. Circles’ aims are aggregated via the linking roles. Circles consist of the people who do the work of the circle, and each circle is responsible for aligning with the decisions of the other circles for the whole to function well.

In a distributed system, it’s critical that information flows well between circles. Astute linking roles, open, well-documented meetings, and proactive feedback are characteristics of functioning circular organizations. This necessitates right-sizing the number of circles such that silos don’t form and information can flow between all circles easily.

Operational Roles

Circles can designate operational roles for its members to accomplish specific Circle aims. Operational roles, (different from the linking roles) ensure the democratization of burden. The specific responsibilities of each role and who best to serve in the capacity of each role is decided via group process.

Meetings

Great meetings are those in which each participant feels a sense of shared purpose in the meeting's intent and has a clear understanding of why their contribution is welcomed. Meetings in which communications are delivered top-down are best distributed as emails, or only presented in a meeting if there is openness to proposal modification. Meetings are an opportunity to tap the collective intelligence to arrive at an answer superior to any answer a sole individual could have summoned themselves.

Check-ins

Check-ins are an invitation for each participant to share personal updates of their life, either within or outside of the collaborative context. The outset of a meeting is the ideal time to check-in with one another to set a supportive tone for the meeting.

Agenda consent

Before beginning a meeting, each participant is given time to familiarize with the agenda, bring up any adjustments they need to make, and ultimately consent to the agenda.

Understand: Proposal & Questions

Whomever added an agenda item brings forth relevant information as a proposal. The proposal is offered to the group and time is given for questions of clarification and understanding. Once the proposal is clear to everyone, a response round begins.

Reflect: Response Rounds

“Rounds” are a method of turn-taking in group meetings where each member of a team gives their input and the group feels satisfied that the floor time for each individual was evenly distributed. Rounds can be prescriptive in some teams, with allotted speaking durations, or implied, whereby each person in the team is attuned to the expressions of each individual in the team, and consciously yielding the floor to allow members who’ve been less engaged to come forth with what they need to say when they need to say it. Research at Google demonstrated that teams with egalitarian distribution of floor time flourished while those where conversation was dominated by a few individuals fell short of their goals. (Duhigg, 2016)

In Part 3 we’ll explore a practice integral to Sociocracy: fielding and resolving objections to reach consent. Until then, thank you for reading!

Bibliography

Duhigg, C. (2016, February 25). What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team. The New York Times

Rau, T. (2019, June 21). On Objections in Sociocracy—Sociocracy For All

Rau, T. (2019, December 1). Saying yes! To working and no! To stumbling blocks—Sociocracy For All

Rau, T. J. (2023). Sociocracy—A Brief Introduction. Sociocracy For All.